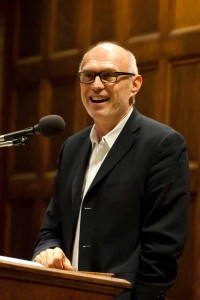

Der Yale-Professor Dr. Miroslav Volf gilt als einer der bedeutendsten Theologen weltweit. Am 15. & 16. März 2013 ist er zu Gast in Marburg. Sein Thema: “Transformation und Versöhnung: Öffentlich glauben in einer pluralistischen Welt.” Ich konnte schon mal vorab ein kurzes Interview mit ihm führen:

Professor Volf, according to Christianity Today your book “Exclusion & Embrace” is one of the 100 most important religious books of the 20th century and is finally being published in German. Could you tell us briefly why reconciliation is an important issue for us today?

If we were self-enclosed individuals, related to other individuals only in external ways, reconciliation would be of little importance. But our lives are intertwined and our interactions shape who we are. Broken relationships means broken selves. That’s were reconciliation comes in. Add to this that we live in a globalized world in which very diverse people increasingly live “under the same roof.” Differences among people are source of richness, but also of conflict. Reconciliation is central to the Christian faith since our faith’s most fundamental claim is that God is love.

In our globalized world, what are the biggest challenges for Christians today?

Reconciliation is obviously a challenge, in particular it is a challenge in an environment of differences among religions and overarching interpretations of life. As a result of globalization, the world has contracted and religions have asserted themselves. Differences, including differences among religions, are one source of conflict; and these differences are also one reason why it is difficult to reconcile, for we understand reconciliation partly differently. A related challenge, a more fundamental one I think, concerns the idea of a flourishing life. The most fundamental human question is, What kind of life is genuinely flourishing human life? Diverse religions give diverse—more precisely: partly diverse—answers to this question. That’s a challenge. And on top of it comes the nest: there are powerful currents in our culture, partly shaped by globalization, which lead us not just to answer the question about human flourishing wrongly—judged, for me, from the vantage point of the Christian faith—but not to ask it at all. Consumption, the most potent opiate of the people, for instance, often replaces the pursuit of a life worth living. In its central concern, the faith then becomes irrelevant.

You will come to Germany in March 2013 – not for the first time, though. What memories do you have of Germany?

I have studied and done research in Germany for a decade or so—mainly in the beautiful Tübingen. I have wonderful memories of my life in Germany, and many very good friends. I had scholarships, first from the Diakonishes Werk and then from the Alexander von Humboldt Stiftung. My early academic work would have been unthinkable without the stimulating intellectual environment, rich cultural heritage, generous financial support, and many friendly encounters that I had in Germany. My father was partly German, which meant that while in Germany I was discovering my own heritage as well.

During the study days we will also think about what role Christians should play in society. Why are Christians important for successful social life within society?

An important word in your question is “should.” Christians are important for successful social life if they insert themselves into the public life in a way they should. But often Christians don’t. Sometimes they withdraw, and their faith betrays its own character by idling, not contributing, not serving the common good. At other times Christians do get involved, but think that they have to remake everything in their own image, forgetting that they need to respect the same rights of others that they claim for themselves. When this happens, Christians do more harm than good, to themselves and to others. But there are settings—such as in predominantly secular societies or in societies dominated by different religion—in which the right of Christians to articulate publicly vision of the good life and to work for it is not respected. Christians are then treated unfairly, sometimes even persecuted, and the common good suffers. In my judgment, the most important contribution of the Christian faith to the public life is to be the guardians of authentic humanity—to articulate always afresh, embody, and keep alive a vision of human flourishing rooted in the story of Jesus Christ and the reality of the Triune God.

Thanks so much! Looking forward to see you in Marburg.

Das Interview auf Deutsch gibt es hier.

Wer sich inhaltlich mit dem Thema Versöhnung, Inklusion und Identität auseinandersetzen möchte, sollte zum exzellenten Buch von Miroslav Volf greifen: „Von der Ausgrenzung zur Umarmung. Versöhnendes Handeln alsAusdruck christlicher Identität.“

Infos & Anmeldung zum Studientag.

Ja, guter Mann. 🙂

Spontaner Gedanke dazu:

Im Bestreben “kulturell relevant” zu sein, haben Gemeinden im vergangenen Jahrzehnt oft nur an der Oberfläche, der Gottesdienstgestaltung herumgedoktert. Damit ist “religiöser Konsum” nur eine gesellschaftliche Konsummöglichkeit von vielen und Lenin hat auf eine Weise Recht behalten, die er unmöglich ahnen konnte. 😉

Ja, “Folklore statt Kontextualisierung” 🙂